The best pilots of World War II. Luftwaffe aces!! (historical photos)

Our ace pilots during the Great Patriotic War terrified the Germans. The exclamation “Akhtung! Akhtung! Pokryshkin is in the sky!” became widely known. But Alexander Pokryshkin was not the only Soviet ace. We remembered the most productive ones.

Ivan Nikitovich Kozhedub

Ivan Kozhedub was born in 1920 in the Chernigov province. He is considered the most successful Russian fighter pilot in personal combat, with 64 aircraft shot down. The start of the famous pilot’s career was unsuccessful; in the very first battle, his plane was seriously damaged by an enemy Messerschmitt, and when returning to base, he was mistakenly fired upon by Russian anti-aircraft gunners, and only by a miracle did he manage to land. The plane could not be restored, and they even wanted to repurpose the unlucky newcomer, but the regiment commander stood up for him. Only during his 40th combat mission on Kursk Bulge Kozhedub, having already become a “father” - deputy squadron commander, shot down his first “laptezhnik”, as ours called the German “Junkers”. After that, the count went to tens.

Kozhedub fought his last battle in the Great Patriotic War, in which he shot down 2 FW-190s, in the skies over Berlin. In addition, Kozhedub also has two shot down in 1945. American aircraft"Mustang", which attacked him, mistaking his fighter for a German plane. The Soviet ace acted according to the principle that he professed even when working with cadets - “any unknown aircraft is an enemy.” Throughout the war, Kozhedub was never shot down, although his plane often received very serious damage.

Alexander Ivanovich Pokryshkin

Pokryshkin is one of the most famous aces of Russian aviation. Born in 1913 in Novosibirsk. He won his first victory on the second day of the war, shooting down a German Messerschmitt. In total, he has 59 planes shot down personally and 6 in a group. However, this is only official statistics, because, as the commander of an air regiment, and then an air division, Pokryshkin sometimes gave downed planes to young pilots in order to encourage them in this way.

His notebook, entitled “Fighter Tactics in Combat,” became a veritable manual for air warfare. They say that the Germans warned about the appearance of the Russian ace with the phrase: “Akhtung! Achtung! Pokryshkin in the air." The one who shot down Pokryshkin was promised a big reward, but the Russian pilot turned out to be too tough for the Germans. Pokryshkin is considered the inventor of the “Kuban whatnot” - a tactical method of air combat; the Germans nicknamed him the “Kuban escalator”, since the planes arranged in pairs resembled a giant staircase. In the battle, German planes leaving the first stage came under attack from the second, and then the third stage. His other favorite techniques were the falcon kick and the high-speed swing. It is worth noting that Pokryshkin won most of his victories in the first years of the war, when the Germans had a significant superiority in the air.

Nikolay Dmitrievich Gulaev

Born in 1918 in the village of Aksayskaya near Rostov. His first battle is reminiscent of the feat of the Grasshopper from the movie “Only Old Men Go to Battle”: without an order, for the first time in his life, taking off at night under the howl of an air raid on his Yak, he managed to shoot down a German Heinkel night fighter. For such self-will, he was punished and presented with a reward.

Subsequently, Gulaev usually did not limit himself to one downed plane per mission; three times he scored four victories in a day, twice destroyed three planes, and made a double in seven battles. In total, he shot down 57 aircraft personally and 3 in a group. Gulaev rammed one enemy plane when it ran out of ammunition, after which he himself got into a tailspin and barely had time to eject. His risky style of fighting became a symbol of the romantic trend in the art of aerial combat.

Grigory Andreevich Rechkalov

Born in 1920 in the Perm province. On the eve of the war, a slight degree of color blindness was discovered at the medical flight commission, but the regiment commander did not even look at the medical report - pilots were very much needed. He won his first victory on the outdated I-153 biplane number 13, which was unlucky for the Germans, as he joked. Then he ended up in Pokryshkin’s group and was trained on the Airacobra, an American fighter that became famous for its tough temperament - it very easily went into a tailspin at the slightest mistake by the pilot; the Americans themselves were reluctant to fly such aircraft. In total, he shot down 56 aircraft personally and 6 in a group. Perhaps no other ace of ours personally has such a variety of types of downed aircraft as Rechkalov, these include bombers, attack aircraft, reconnaissance aircraft, fighters, transport aircraft, and relatively rare trophies - “Savoy” and PZL -24.

Georgy Dmitrievich Kostylev

Born in Oranienbaum, present-day Lomonosov, in 1914. He began his flight practice in Moscow at the legendary Tushinsky airfield, where the Spartak stadium is now being built. The legendary Baltic ace, who covered the skies over Leningrad and won the largest number of victories in naval aviation, personally shot down at least 20 enemy aircraft and 34 in the group.

He shot down his first Messerschmitt on July 15, 1941. He fought on a British Hurricane, received under lend-lease, on the left side of which there was a large inscription “For Rus'!” In February 1943, he ended up in a penal battalion for causing destruction in the house of a major in the quartermaster service. Kostylev was amazed by the abundance of dishes with which he treated his guests, and could not restrain himself, since he knew first-hand what was happening in the besieged city. He was deprived of his awards, demoted to the Red Army and sent to the Oranienbaum bridgehead, to the places where he spent his childhood. Penalties saved the hero, and already in April he again takes his fighter into the air and wins victory over the enemy. Later he was reinstated in rank and his awards were returned, but he never received the second Hero Star.

Maresyev Alexey Petrovich

A legendary man, who became the prototype of the hero of Boris Polevoy’s story “The Tale of a Real Man,” a symbol of the courage and perseverance of the Russian warrior. Born in 1916 in the city of Kamyshin, Saratov province. In a battle with the Germans, his plane was shot down, and the pilot, wounded in the legs, managed to land on territory occupied by the Germans. After which he crawled to his people for 18 days, in the hospital both legs were amputated. But Maresyev managed to return to duty, he learned to walk on prosthetics and took to the skies again. At first they didn’t trust him; anything can happen in battle, but Maresyev proved that he could fight no worse than others. As a result, to the 4 German planes shot down before the injury, 7 more were added. Polevoy’s story about Maresyev was allowed to be published only after the war, so that the Germans, God forbid, would not think that there was no one to fight in the Soviet army, they had to send disabled people.

Popkov Vitaly Ivanovich

This pilot also cannot be ignored, because it was he who became one of the most famous incarnations of an ace pilot in cinema - the prototype of the famous Maestro from the film “Only Old Men Go to Battle.” The “Singing Squadron” actually existed in the 5th Guards Fighter Aviation Regiment, where Popkov served, it had its own choir, and two aircraft were given to it by Leonid Utesov himself.

Popkov was born in Moscow in 1922. He won his first victory in June 1942 over the city of Kholm. He took part in battles on the Kalinin Front, on the Don and the Kursk Bulge. In total, he flew 475 combat missions, conducted 117 air battles, and personally shot down 41 enemy aircraft plus 1 in the group. On the last day of the war, Popkov, in the skies over Brno, shot down the legendary German Hartmann, the most successful ace of World War II, but he managed to land and survive, however, this still did not save him from captivity. Popkov's popularity was so great that during his lifetime a monument was erected to him in Moscow.

The title ace, in reference to military pilots, first appeared in French newspapers during the First World War. In 1915 journalists nicknamed them “aces”, and translated from french word"as" means "ace", pilots who have shot down three or more enemy aircraft. The legendary French pilot Roland Garros was the first to be called an ace.

The most experienced and successful pilots in the Luftwaffe were called experts - “Experte”

Luftwaffe

Eric Alfred Hartman (Boobie)

Erich Hartmann (German: Erich Hartmann; April 19, 1922 - September 20, 1993) was a German ace pilot, considered the most successful fighter pilot in the history of aviation. According to German data, during the Second World War he shot down “352” enemy aircraft (of which 345 were Soviet) in 825 air battles.

Hartmann graduated from flight school in 1941 and was assigned to the 52nd Fighter Squadron in October 1942. Eastern Front. His first commander and mentor was the famous Luftwaffe expert Walter Krupinsky.

Hartmann shot down his first plane on November 5, 1942 (an Il-2 from the 7th GShAP), but over the next three months he managed to shoot down only one plane. Hartmann gradually improved his flying skills, focusing on the effectiveness of the first attack

Oberleutnant Erich Hartmann in the cockpit of his fighter, the famous emblem of the 9th Staffel of the 52nd Squadron is clearly visible - a heart pierced by an arrow with the inscription “Karaya”, in the upper left segment of the heart the name of Hartman’s bride “Ursel” is written (the inscription is almost invisible in the picture) .

German ace Hauptmann Erich Hartmann (left) and Hungarian pilot Laszlo Pottiondy. German fighter pilot Erich Hartmann - the most successful ace of World War II

Krupinski Walter is the first commander and mentor of Erich Hartmann!!

Hauptmann Walter Krupinski commanded the 7th Staffel of the 52nd Squadron from March 1943 to March 1944. Pictured is Krupinski wearing the Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves, which he received on March 2, 1944 for 177 victories in air combat. Shortly after this photo was taken, Krupinski was transferred to the West, where he served with the 7-5, JG-11 and JG-26, ending the war in an Me-262 with J V-44.

In the photo from March 1944, from left to right: commander of 8./JG-52 Lieutenant Friedrich Obleser, commander of 9./JG-52 Lieutenant Erich Hartmann. Lieutenant Karl Gritz.

Wedding of Luftwaffe ace Erich Hartmann (1922 - 1993) and Ursula Paetsch. To the left of the couple is Hartmann's commander, Gerhard Barkhorn (1919 - 1983). On the right is Hauptmann Wilhelm Batz (1916 - 1988).

Bf. 109G-6 Hauptmann Erich Hartmann, Buders, Hungary, November 1944.

Barkhorn Gerhard "Gerd"

Major Barkhorn Gerhard

He began flying with JG2 and was transferred to JG52 in the fall of 1940. From January 16, 1945 to April 1, 1945 he commanded JG6. He ended the war in the “squadron of aces” JV 44, when on 04/21/1945 his Me 262 was shot down while landing by American fighters. He was seriously wounded and was held captive by the Allies for four months.

Number of victories - 301. All victories on the Eastern Front.

Hauptmann Erich Hartmann (04/19/1922 - 09/20/1993) with his commander Major Gerhard Barkhorn (05/20/1919 - 01/08/1983) studying the map. II./JG52 (2nd group of the 52nd fighter squadron). E. Hartmann and G. Barkhorn are the most successful pilots of the Second World War, having 352 and 301 aerial victories, respectively. In the lower left corner of the photo is E. Hartmann’s autograph.

The Soviet fighter LaGG-3, destroyed by German aircraft while still on the railway platform.

The snow melted faster than the white winter color was washed off the Bf 109. The fighter takes off right through the spring puddles.)!.

Captured Soviet airfield: I-16 stands next to Bf109F from II./JG-54.

In tight formation, a Ju-87D bomber from StG-2 “Immelmann” and “Friedrich” from I./JG-51 are carrying out a combat mission. At the end of the summer of 1942, the pilots of I./JG-51 switched to FW-190 fighters.

Commander of the 52nd Fighter Squadron (Jagdgeschwader 52) Lieutenant Colonel Dietrich Hrabak, commander of the 2nd Group of the 52nd Fighter Squadron (II.Gruppe / Jagdgeschwader 52) Hauptmann Gerhard Barkhorn and an unknown Luftwaffe officer with a Messerschmitt fighter Bf.109G-6 at Bagerovo airfield.

Walter Krupinski, Gerhard Barkhorn, Johannes Wiese and Erich Hartmann

The commander of the 6th Fighter Squadron (JG6) of the Luftwaffe, Major Gerhard Barkhorn, in the cockpit of his Focke-Wulf Fw 190D-9 fighter.

Bf 109G-6 “double black chevron” of I./JG-52 commander Hauptmann Gerhard Barkhorn, Kharkov-Yug, August 1943.

Please note given name airplane; Christi is the name of the wife of Barkhorn, the second most successful fighter pilot in the Luftwaffe. The picture shows the plane Barkhorn flew in when he was commander of I./JG-52, when he had not yet crossed the 200-victory mark. Barkhorn survived; in total he shot down 301 aircraft, all on the eastern front.

Gunther Rall

German ace fighter pilot Major Günther Rall (03/10/1918 - 10/04/2009). Günther Rall was the third most successful German ace of World War II. He has 275 air victories (272 on the Eastern Front) in 621 combat missions. Rall himself was shot down 8 times. On the pilot’s neck is visible the Knight’s Cross with oak leaves and swords, which he was awarded on September 12, 1943 for 200 air victories.

“Friedrich” from III./JG-52, this group in the initial phase of Operation Barbarossa covered the troops of the countries operating in the coastal zone of the Black Sea. Note the unusual angular tail number “6” and the “sine wave”. Apparently, this plane belonged to the 8th Staffel.

Spring 1943, Rall looks on approvingly as Lieutenant Josef Zwernemann drinks wine from a bottle

Günther Rall (second from left) after his 200th aerial victory. Second from right - Walter Krupinski

Shot down Bf 109 of Günter Rall

Rall in his Gustav IV

After being seriously wounded and partially paralyzed, Oberleutnant Günther Rall returned to 8./JG-52 on 28 August 1942, and two months later he became a Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves. Rall ended the war, taking an honorable third place in performance among Luftwaffe fighter pilots

won 275 victories (272 on the Eastern Front); shot down 241 Soviet fighters. He flew 621 combat missions, was shot down 8 times and wounded 3 times. His Messerschmitt had the personal number "Devil's Dozen"

The commander of the 8th squadron of the 52nd fighter squadron (Staffelkapitän 8.Staffel/Jagdgeschwader 52), Oberleutnant Günther Rall (Günther Rall, 1918-2009), with the pilots of his squadron, during a break between combat missions, plays with the squadron’s mascot - a dog named “Rata” .

In the photo in the foreground from left to right: non-commissioned officer Manfred Lotzmann, non-commissioned officer Werner Höhenberg, and lieutenant Hans Funcke.

In the background, from left to right: Oberleutnant Günther Rall, Lieutenant Hans Martin Markoff, Sergeant Major Karl-Friedrich Schumacher and Oberleutnant Gerhard Luety.

The picture was taken by frontline correspondent Reissmüller on March 6, 1943 near the Kerch Strait.

photo of Rall and his wife Hertha, originally from Austria

Third in the triumvirate the best experts The 52nd Squadron was listed as Günter Rall. Rall flew a black fighter with tail number “13” after his return to service on August 28, 1942 after being seriously wounded in November 1941. By this time, Rall had 36 victories to his name. Before being transferred to the West in the spring of 1944, he shot down another 235 Soviet aircraft. Pay attention to the symbols of III./JG-52 - the emblem on the front of the fuselage and the “sine wave” drawn closer to the tail.

Kittel Otto (Bruno)

Otto Kittel (Otto "Bruno" Kittel; February 21, 1917 - February 14, 1945) was a German ace pilot, fighter, and participant in World War II. He flew 583 combat missions and scored 267 victories, which is the fourth most in history. Luftwaffe record holder for the number of shot down Il-2 attack aircraft - 94. Awarded the Knight's Cross with oak leaves and swords.

in 1943, luck turned his face. On January 24, he shot down the 30th plane, and on March 15, the 47th. On the same day, his plane was seriously damaged and fell 60 km behind the front line. In thirty-degree frost on the ice of Lake Ilmen, Kittel went out to his own.

So Kittel Otto returned from four day's journey!! His plane was shot down behind the front line, 60 km away!!

Otto Kittel on vacation, summer 1941. At that time, Kittel was an ordinary Luftwaffe pilot with the rank of non-commissioned officer.

Otto Kittel in the circle of comrades! (marked with a cross)

At the head of the table is "Bruno"

Otto Kittel with his wife!

Killed on February 14, 1945 during an attack by a Soviet Il-2 attack aircraft. Shot down by the gunner's return fire, Kittel's Fw 190A-8 (serial number 690 282) crashed into a swampy area near Soviet troops and exploded. The pilot did not use a parachute because he died in the air.

Two Luftwaffe officers bandage the hand of a wounded Red Army prisoner near a tent

Airplane "Bruno"

Novotny Walter (Novi)

German ace pilot of World War II, during which he flew 442 combat missions, scoring 258 air victories, of which 255 on the Eastern Front and 2 over 4-engine bombers. The last 3 victories were won while flying the Me.262 jet fighter. He scored most of his victories flying the FW 190, and approximately 50 victories in the Messerschmitt Bf 109. He was the first pilot in the world to score 250 victories. Awarded the Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds

Representatives of the Soviet air force made a huge contribution to the defeat of the Nazi invaders. Many pilots gave their lives for the freedom and independence of our Motherland, many became Heroes Soviet Union. Some of them forever entered the elite of the Russian Air Force, the illustrious cohort of Soviet aces - the threat of the Luftwaffe. Today we remember the 10 most successful Soviet fighter pilots, who accounted for the most enemy aircraft shot down in air battles.

On February 4, 1944, the outstanding Soviet fighter pilot Ivan Nikitovich Kozhedub was awarded the first star of the Hero of the Soviet Union. By the end of the Great Patriotic War, he was already three times Hero of the Soviet Union. During the war years, only one more Soviet pilot was able to repeat this achievement - it was Alexander Ivanovich Pokryshkin. But the history of Soviet fighter aviation during the war does not end with these two most famous aces. During the war, another 25 pilots were twice nominated for the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, not to mention those who were once awarded this highest military award in the country of those years.

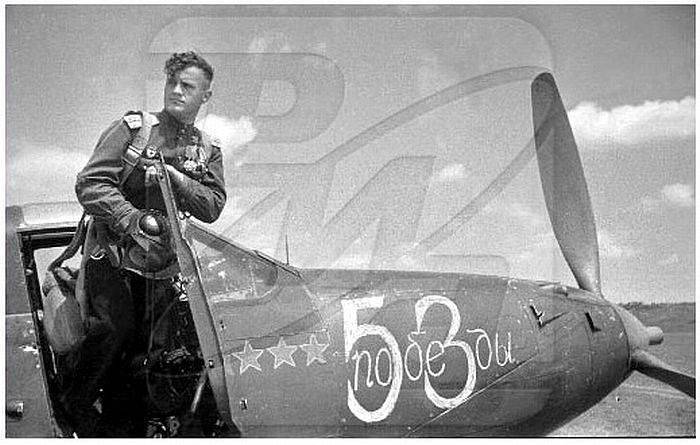

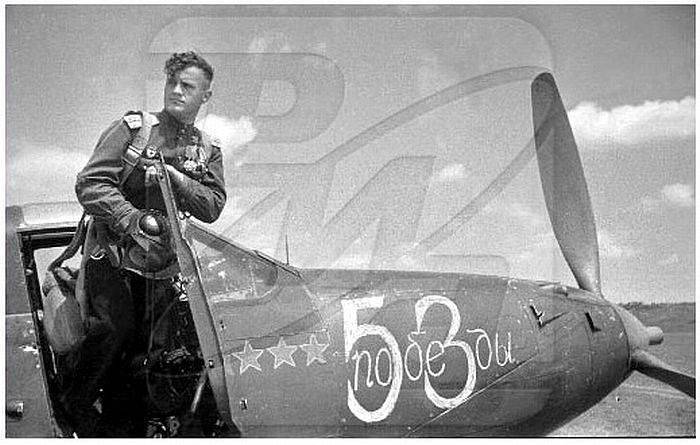

Ivan Nikitovich Kozhedub

During the war, Ivan Kozhedub made 330 combat missions, conducted 120 air battles and personally shot down 64 enemy aircraft. He flew on La-5, La-5FN and La-7 aircraft.

Official Soviet historiography listed 62 downed enemy aircraft, but archival research showed that Kozhedub shot down 64 aircraft (for some reason, two air victories were missing - April 11, 1944 - PZL P.24 and June 8, 1944 - Me 109) . Among the trophies of the Soviet ace pilot were 39 fighters (21 Fw-190, 17 Me-109 and 1 PZL P.24), 17 dive bombers (Ju-87), 4 bombers (2 Ju-88 and 2 He-111), 3 attack aircraft (Hs-129) and one Me-262 jet fighter. In addition, in his autobiography, he indicated that in 1945 he shot down two American P-51 Mustang fighters, which attacked him from a long distance, mistaking him for a German plane.

In all likelihood, if Ivan Kozhedub (1920-1991) had started the war in 1941, his count of downed aircraft could have been even higher. However, his debut came only in 1943, and the future ace shot down his first plane in the battle of Kursk. On July 6, during a combat mission, he shot down a German Ju-87 dive bomber. Thus, the pilot’s performance is truly amazing; in just two war years he managed to bring his victories to a record in the Soviet Air Force.

At the same time, Kozhedub was never shot down during the entire war, although he returned to the airfield several times in a heavily damaged fighter. But the last could have been his first air battle, which took place on March 26, 1943. His La-5 was damaged by a burst from a German fighter; the armored back saved the pilot from an incendiary shell. And upon returning home, his plane was fired upon by its own air defense, and the car received two hits. Despite this, Kozhedub managed to land the plane, which could no longer be fully restored.

The future best Soviet ace took his first steps in aviation while studying at the Shotkinsky flying club. At the beginning of 1940, he was drafted into the Red Army and in the fall of the same year he graduated from the Chuguev Military Aviation School of Pilots, after which he continued to serve in this school as an instructor. With the beginning of the war, the school was evacuated to Kazakhstan. The war itself began for him in November 1942, when Kozhedub was seconded to the 240th Fighter Aviation Regiment of the 302nd Fighter Aviation Division. The formation of the division was completed only in March 1943, after which it flew to the front. As mentioned above, he won his first victory only on July 6, 1943, but a start had been made.

Already on February 4, 1944, senior lieutenant Ivan Kozhedub was awarded the title of Hero of the Soviet Union, at that time he managed to fly 146 combat missions and shoot down 20 enemy aircraft in air battles. He received his second star in the same year. He was presented for the award on August 19, 1944 for 256 combat missions and 48 downed enemy aircraft. At that time, as a captain, he served as deputy commander of the 176th Guards Fighter Aviation Regiment.

In air battles, Ivan Nikitovich Kozhedub was distinguished by fearlessness, composure and automatic piloting, which he brought to perfection. Perhaps the fact that before being sent to the front he spent several years as an instructor played a very large role in his future successes in the sky. Kozhedub could easily conduct aimed fire at the enemy at any position of the aircraft in the air, and also easily performed complex aerobatics. Being an excellent sniper, he preferred to conduct air combat at a distance of 200-300 meters.

Ivan Nikitovich Kozhedub won his last victory in the Great Patriotic War on April 17, 1945 in the skies over Berlin, in this battle he shot down two German FW-190 fighters. The future air marshal (title awarded on May 6, 1985), Major Kozhedub, became a three-time Hero of the Soviet Union on August 18, 1945. After the war, he continued to serve in the country's Air Force and went through a very serious career path, bringing many more benefits to the country. The legendary pilot died on August 8, 1991, and was buried at the Novodevichy cemetery in Moscow.

Alexander Ivanovich Pokryshkin

Alexander Ivanovich Pokryshki fought from the very first day of the war to the last. During this time, he made 650 combat missions, in which he conducted 156 air battles and officially personally shot down 59 enemy aircraft and 6 aircraft in the group. Is the second highest scoring ace in the countries anti-Hitler coalition after Ivan Kozhedub. During the war he flew MiG-3, Yak-1 and American P-39 Airacobra aircraft.

The number of aircraft shot down is very arbitrary. Quite often, Alexander Pokryshkin made deep raids behind enemy lines, where he also managed to win victories. However, only those that could be confirmed by ground services were counted, that is, if possible, over their territory. He could have had 8 such unaccounted victories in 1941 alone. Moreover, they accumulated throughout the war. Also, Alexander Pokryshkin often gave the planes he shot down at the expense of his subordinates (mostly wingmen), thus stimulating them. In those years this was quite common.

Already during the first weeks of the war, Pokryshkin was able to understand that the tactics of the Soviet Air Force were outdated. Then he began to write down his notes on this matter in a notebook. He kept a careful record of the air battles in which he and his friends took part, after which he made detailed analysis written. Moreover, at that time he had to fight in very difficult conditions of constant retreat of Soviet troops. He later said: “Those who did not fight in 1941-1942 do not know the real war.”

After the collapse of the Soviet Union and massive criticism of everything that was associated with that period, some authors began to “cut down” the number of Pokryshkin’s victories. This was also due to the fact that at the end of 1944, official Soviet propaganda finally made the pilot “a bright image of a hero, the main fighter of the war.” In order not to lose the hero in a random battle, it was ordered to limit the flights of Alexander Ivanovich Pokryshkin, who by that time already commanded the regiment. On August 19, 1944, after 550 combat missions and 53 officially won victories, he became a three-time Hero of the Soviet Union, the first in history.

The wave of “revelations” that washed over him after the 1990s also affected him because after the war he managed to take the post of Commander-in-Chief of the country’s air defense forces, that is, he became a “major Soviet official.” If we talk about the low ratio of victories to completed missions, then it can be noted that long time at the beginning of the war, Pokryshkin flew out on his MiG-3, and then the Yak-1, to attack enemy ground forces or perform reconnaissance flights. For example, by mid-November 1941, the pilot had already completed 190 combat missions, but the vast majority of them - 144 - were to attack enemy ground forces.

Alexander Ivanovich Pokryshkin was not only a cold-blooded, brave and virtuoso Soviet pilot, but also a thinking pilot. He was not afraid to criticize the existing tactics of using fighter aircraft and advocated its replacement. Discussions on this matter with the regiment commander in 1942 led to the fact that the ace pilot was even expelled from the party and the case was sent to the tribunal. The pilot was saved by the intercession of the regiment commissar and higher command. The case against him was dropped and he was reinstated in the party. After the war, Pokryshkin had a long conflict with Vasily Stalin, which had a detrimental effect on his career. Everything changed only in 1953 after the death of Joseph Stalin. Subsequently, he managed to rise to the rank of air marshal, which was awarded to him in 1972. The famous ace pilot died on November 13, 1985 at the age of 72 in Moscow.

Grigory Andreevich Rechkalov

Grigory Andreevich Rechkalov fought from the very first day of the Great Patriotic War. Twice Hero of the Soviet Union. During the war he flew more than 450 combat missions, shooting down 56 enemy aircraft personally and 6 in a group in 122 air battles. According to other sources, the number of his personal aerial victories could exceed 60. During the war, he flew I-153 “Chaika”, I-16, Yak-1, P-39 “Airacobra” aircraft.

Probably no other Soviet fighter pilot had such a variety of downed enemy vehicles as Grigory Rechkalov. Among his trophies were Me-110, Me-109, Fw-190 fighters, Ju-88, He-111 bombers, Ju-87 dive bomber, Hs-129 attack aircraft, Fw-189 and Hs-126 reconnaissance aircraft, as well as such a rare car as the Italian Savoy and the Polish PZL-24 fighter, which was used by the Romanian Air Force.

Surprisingly, the day before the start of the Great Patriotic War, Rechkalov was suspended from flying by decision of the medical flight commission; he was diagnosed with color blindness. But upon returning to his unit with this diagnosis, he was still cleared to fly. The beginning of the war forced the authorities to simply turn a blind eye to this diagnosis, simply ignoring it. At the same time, he served in the 55th Fighter Aviation Regiment since 1939 together with Pokryshkin.

This brilliant military pilot had a very contradictory and uneven character. Showing an example of determination, courage and discipline in one mission, in another he could be distracted from the main task and just as decisively begin the pursuit of a random enemy, trying to increase the score of his victories. His combat fate in the war was closely intertwined with the fate of Alexander Pokryshkin. He flew with him in the same group, replacing him as squadron commander and regiment commander. Pokryshkin himself best qualities Grigory Rechkalov believed in frankness and directness.

Rechkalov, like Pokryshkin, fought since June 22, 1941, but with a forced break of almost two years. In the first month of fighting, he managed to shoot down three enemy aircraft in his outdated I-153 biplane fighter. He also managed to fly on the I-16 fighter. On July 26, 1941, during a combat mission near Dubossary, he was wounded in the head and leg by fire from the ground, but managed to bring his plane to the airfield. After this injury, he spent 9 months in the hospital, during which time the pilot underwent three operations. And in once again The medical commission tried to put an insurmountable obstacle on the path of the future famous ace. Grigory Rechkalov was sent to serve in a reserve regiment, which was equipped with U-2 aircraft. The future twice Hero of the Soviet Union took this direction as a personal insult. At the district Air Force headquarters, he managed to ensure that he was returned to his regiment, which at that time was called the 17th Guards Fighter Aviation Regiment. But very soon the regiment was recalled from the front to be re-equipped with new American Airacobra fighters, which were sent to the USSR as part of the Lend-Lease program. For these reasons, Rechkalov began to beat the enemy again only in April 1943.

Grigory Rechkalov, being one of the domestic stars of fighter aviation, was perfectly able to interact with other pilots, guessing their intentions and working together as a group. Even during the war years, a conflict arose between him and Pokryshkin, but he never sought to throw out any negativity about this or blame his opponent. On the contrary, in his memoirs he spoke well of Pokryshkin, noting that they managed to unravel the tactics of the German pilots, after which they began to use new techniques: they began to fly in pairs rather than in flights, it was better to use radio for guidance and communication, and echeloned their machines with the so-called “ bookcase."

Grigory Rechkalov won 44 victories in the Airacobra, more than other Soviet pilots. After the end of the war, someone asked the famous pilot what he valued most in the Airacobra fighter, on which so many victories were won: the power of the fire salvo, speed, visibility, reliability of the engine? To this question, the ace pilot replied that all of the above, of course, mattered; these were the obvious advantages of the aircraft. But the main thing, according to him, was the radio. The Airacobra had excellent radio communication, rare in those years. Thanks to this connection, pilots in battle could communicate with each other, as if on the phone. Someone saw something - immediately all members of the group are aware. Therefore, we did not have any surprises during combat missions.

After the end of the war, Grigory Rechkalov continued his service in the Air Force. True, not as long as other Soviet aces. Already in 1959, he retired to the reserve with the rank of major general. After which he lived and worked in Moscow. He died in Moscow on December 20, 1990 at the age of 70.

Nikolay Dmitrievich Gulaev

Nikolai Dmitrievich Gulaev found himself on the fronts of the Great Patriotic War in August 1942. In total, during the war years he made 250 sorties, conducted 49 air battles, in which he personally destroyed 55 enemy aircraft and 5 more aircraft in the group. Such statistics make Gulaev the most effective Soviet ace. For every 4 missions he had a plane shot down, or on average more than one plane for every air battle. During the war, he flew I-16, Yak-1, P-39 Airacobra fighters; most of his victories, like Pokryshkin and Rechkalov, he won on the Airacobra.

Twice Hero of the Soviet Union Nikolai Dmitrievich Gulaev shot down not much fewer planes than Alexander Pokryshkin. But in terms of effectiveness of fights, he far surpassed both him and Kozhedub. Moreover, he fought for less than two years. At first, in the deep Soviet rear, as part of the air defense forces, he was engaged in the protection of important industrial facilities, protecting them from enemy air raids. And in September 1944, he was almost forcibly sent to study at the Air Force Academy.

The Soviet pilot performed his most effective battle on May 30, 1944. In one air battle over Skuleni, he managed to shoot down 5 enemy aircraft at once: two Me-109, Hs-129, Ju-87 and Ju-88. During the battle, he himself was seriously wounded in his right arm, but concentrating all his strength and will, he was able to bring his fighter to the airfield, bleeding, landed and, having taxied to the parking lot, lost consciousness. The pilot only came to his senses in the hospital after the operation, and here he learned that he had been awarded the second title of Hero of the Soviet Union.

The entire time Gulaev was at the front, he fought desperately. During this time, he managed to make two successful rams, after which he managed to land his damaged plane. He was wounded several times during this time, but after being wounded he invariably returned back to duty. At the beginning of September 1944, the ace pilot was forcibly sent to study. At that moment, the outcome of the war was already clear to everyone and they tried to protect the famous Soviet aces by ordering them to the Air Force Academy. Thus, the war ended unexpectedly for our hero.

Nikolai Gulaev was called the brightest representative“romantic school” of air combat. Often the pilot dared to commit “irrational actions” that shocked the German pilots, but helped him win victories. Even among other far from ordinary Soviet fighter pilots, the figure of Nikolai Gulaev stood out for its colorfulness. Only such a person, possessing unparalleled courage, would be able to conduct 10 super-effective air battles, recording two of his victories by successfully ramming enemy aircraft. Gulaev's modesty in public and in his self-esteem was dissonant with his exceptionally aggressive and persistent manner of conducting air combat, and he managed to carry openness and honesty with boyish spontaneity throughout his life, retaining some youthful prejudices until the end of his life, which did not prevent him from rising to the rank of rank of Colonel General of Aviation. The famous pilot died on September 27, 1985 in Moscow.

Kirill Alekseevich Evstigneev

Kirill Alekseevich Evstigneev twice Hero of the Soviet Union. Like Kozhedub, he began his military career relatively late, only in 1943. During the war years, he made 296 combat missions, conducted 120 air battles, personally shooting down 53 enemy aircraft and 3 in the group. He flew La-5 and La-5FN fighters.

The almost two-year “delay” in appearing at the front was due to the fact that the fighter pilot suffered from a stomach ulcer, and with this disease he was not allowed to go to the front. Since the beginning of the Great Patriotic War, he worked as an instructor at a flight school, and after that he drove Lend-Lease Airacobras. Working as an instructor gave him a lot, as it did for others Soviet ace Kozhedub. At the same time, Evstigneev did not stop writing reports to the command with a request to send him to the front, as a result they were nevertheless satisfied. Kirill Evstigneev received his baptism of fire in March 1943. Like Kozhedub, he fought as part of the 240th Fighter Aviation Regiment and flew the La-5 fighter. On his first combat mission, on March 28, 1943, he scored two victories.

During the entire war, the enemy never managed to shoot down Kirill Evstigneev. But he got it twice from his own people. The first time the Yak-1 pilot, carried away by air combat, crashed into his plane from above. The Yak-1 pilot immediately jumped out of the plane, which had lost one wing, with a parachute. But Evstigneev’s La-5 suffered less damage, and he managed to bring the plane to the positions of his troops, landing the fighter next to the trenches. The second incident, more mysterious and dramatic, occurred over our territory in the absence of enemy aircraft in the air. The fuselage of his plane was pierced by a burst, damaging Evstigneev’s legs, the car caught fire and went into a dive, and the pilot had to jump from the plane with a parachute. At the hospital, doctors were inclined to amputate the pilot’s foot, but he filled them with such fear that they abandoned their idea. And after 9 days, the pilot escaped from the hospital and with crutches reached the location of his native unit 35 kilometers.

Kirill Evstigneev constantly increased the number of his aerial victories. Until 1945, the pilot was ahead of Kozhedub. At the same time, the unit doctor periodically sent him to the hospital to treat an ulcer and a wounded leg, which the ace pilot terribly resisted. Kirill Alekseevich was seriously ill since pre-war times; in his life he underwent 13 surgical operations. Very often the famous Soviet pilot flew, overcoming physical pain. Evstigneev, as they say, was obsessed with flying. In his free time, he tried to train young fighter pilots. He was the initiator of training air battles. For the most part, his opponent in them was Kozhedub. At the same time, Evstigneev was completely devoid of any sense of fear, even at the very end of the war he calmly launched a frontal attack on the six-gun Fokkers, winning victories over them. Kozhedub spoke of his comrade in arms like this: “Flint pilot.”

Captain Kirill Evstigneev ended the Guard War as a navigator of the 178th Guards Fighter Aviation Regiment. The pilot spent his last battle in the skies of Hungary on March 26, 1945, on his fifth La-5 fighter of the war. After the war, he continued to serve in the USSR Air Force, retired in 1972 with the rank of major general, and lived in Moscow. He died on August 29, 1996 at the age of 79, and was buried at the Kuntsevo cemetery in the capital.

Sources of information:

http://svpressa.ru

http://airaces.narod.ru

http://www.warheroes.ru

Ctrl Enter

Noticed osh Y bku Select text and click Ctrl+Enter

Luftwaffe Aces

At the suggestion of some Western authors, carefully accepted by domestic compilers, German aces are considered the most effective fighter pilots of the Second World War, and, accordingly, in history, who achieved fabulous success in air battles. Only the aces Nazi Germany and their Japanese allies are charged with winning accounts containing over a hundred aircraft. But if the Japanese have only one such pilot - they fought with the Americans, then the Germans have as many as 102 pilots who “won” more than 100 victories in the air. Most German pilots, with the exception of fourteen: Heinrich Baer, Hans-Joachim Marseille, Joachim Münchenberg, Walter Oesau, Werner Mölders, Werner Schroer, Kurt Büligen, Hans Hahn, Adolf Galland, Egon Mayer, Joseph Wurmheller and Joseph Priller, as well as night pilots Hans-Wolfgang Schnaufer and Helmut Lent achieved the bulk of their “victories,” of course, on the Eastern Front, and two of them, Erich Hartmann and Gerhard Barkhorn, recorded more than 300 victories.

The total number of air victories achieved by more than 30 thousand German fighter pilots and their allies is mathematically described by the law of large numbers, more precisely, the “Gauss curve”. If we construct this curve only based on the results of the first hundred best German fighters (Germany’s allies will no longer be included there) with a known total number pilots, then the number of victories declared by them will exceed 300-350 thousand, which is four to five times more than the number of victories declared by the Germans themselves - 70 thousand shot down, and catastrophically (to the point of losing all objectivity) exceeds the estimate of sober, politically unbiased historians - 51 a thousand shot down in air battles, of which 32 thousand were on the Eastern Front. Thus, the reliability coefficient of victories of German aces is in the range of 0.15-0.2.

The order for victories for German aces was dictated by the political leadership of Nazi Germany, intensified as the Wehrmacht collapsed, did not formally require confirmation and did not tolerate the revisions adopted in the Red Army. All the “accuracy” and “objectivity” of German claims for victories, so persistently mentioned in the works of some “researchers”, oddly enough, raised and actively published on the territory of Russia, actually comes down to filling out the columns of lengthy and tastefully laid out standard questionnaires, and the writing , even if calligraphic, even if in Gothic font, is in no way connected with aerial victories.

Luftwaffe aces with over 100 victories recorded

Erich HARTMAN (Erich Alfred Bubi Hartmann) - the first Luftwaffe ace in World War II, 352 victories, colonel, Germany.

Erich Hartmann was born on April 19, 1922 in Weissach in Württenberg. His father is Alfred Erich Hartmann, his mother is Elisabeth Wilhelmina Machtholf. He spent his childhood with his younger brother in China, where his father, under the patronage of his cousin- German consul in Shanghai, worked as a doctor. In 1929, frightened by the revolutionary events in China, the Hartmans returned to their homeland.

Since 1936, E. Hartman flew gliders in an aviation club under the guidance of his mother, an athlete pilot. At the age of 14 he received his glider pilot diploma. He piloted airplanes from the age of 16. Since 1940, he trained at the 10th Luftwaffe training regiment in Neukurn near Königsberg, then at the 2nd flight school in the Berlin suburb of Gatow.

After successfully completing the aviation school, Hartman was sent to Zerbst - to the 2nd Fighter Aviation School. In November 1941, Hartmann flew for the first time in the 109 Messerschmitt, the fighter with which he completed his distinguished flying career.

E. Hartman began combat work in August 1942 as part of the 52nd Fighter Squadron, which fought in the Caucasus.

Hartman was lucky. The 52nd was the best German squadron on the Eastern Front. The best German pilots fought in it - Hrabak and von Bonin, Graf and Krupinski, Barkhorn and Rall...

Erich Hartmann was a man of average height, with rich blond hair and bright blue eyes. His character - cheerful and unquestioning, with a good sense of humor, obvious flying skill, the highest art of aerial shooting, perseverance, personal courage and nobility impressed his new comrades.

On October 14, 1942, Hartman went on his first combat mission to the Grozny area. During this flight, Hartman made almost all the mistakes that a young combat pilot can make: he broke away from his wingman and was unable to carry out his orders, opened fire on his planes, got into the fire zone, lost his orientation and landed “on his belly” 30 km away. from your airfield.

20-year-old Hartman scored his first victory on November 5, 1942, shooting down a single-seat Il-2. During the attack by the Soviet attack aircraft, Hartman's fighter was seriously damaged, but the pilot again managed to land the damaged aircraft on its “belly” in the steppe. The plane could not be restored and was written off. Hartman himself immediately “fell ill with a fever” and was admitted to the hospital.

Hartman's next victory was recorded only on January 27, 1943. The victory was recorded over the MiG-1. It was hardly the MiG-1, which were produced and delivered to the troops before the war in a small series of 77 vehicles, but there are plenty of such “overexposures” in German documents. Hartman flies as a wingman with Dammers, Grislavski, Zwerneman. From each of these strong pilots he takes something new, adding to his tactical and flight potential. At the request of Sergeant Major Rossmann, Hartman becomes the wingman of V. Krupinski, an outstanding Luftwaffe ace (197 “victories”, 15th best), distinguished, as it seemed to many, by intemperance and stubbornness.

It was Krupinski who nicknamed Hartman Bubi, in English “Baby” - baby, a nickname that remained with him forever.

Hartmann completed 1,425 Einsatzes and took part in 800 Rabarbars during his career. His 352 victories included many missions with multiple kills of enemy aircraft in one day, his best being six Soviet aircraft shot down on August 24, 1944. This included three Pe-2s, two Yaks, and one Airacobra. The same day turned out to be his best day with 11 victories in two combat missions, during the second mission he became the first person in history to shoot down 300 aircraft in dogfights.

Hartman fought in the skies not only against Soviet aircraft. In the skies of Romania, at the controls of his Bf 109, he also met American pilots. Hartman has several days on his account when he reported several victories at once: on July 7 - about 7 shot down (2 Il-2 and 5 La-5), on August 1, 4 and 5 - about 5, and on August 7 - again about 7 at once (2 Pe-2, 2 La-5, 3 Yak-1). January 30, 1944 - about 6 shot down; February 1 - about 5; March 2 - immediately after 10; May 5 about 6; May 7 about 6; June 1 about 6; June 4 - about 7 Yak-9; June 5 about 6; June 6 - about 5; June 24 - about 5 “Mustangs”; On August 28, he “shot down” 11 Airacobras in a day (Hartman’s daily record); October 27 - 5; November 22 - 6; November 23 - 5; April 4, 1945 - again 5 victories.

After a dozen “victories” “won” on March 2, 1944, E. Hartmann, and with him Chief Lieutenant W. Krupinski, Hauptmann J. Wiese and G. Barkhorn were summoned to the Fuhrer at Berghof to present awards. Lieutenant E. Hartman, who by that time had chalked up 202 “downed” Soviet aircraft, was awarded the Oak Leaves to the Knight’s Cross.

Hartman himself was shot down more than 10 times. Basically, he “faced the wreckage of Soviet planes that he shot down” (a favorite interpretation of his own losses in the Luftwaffe). On August 20, “flying over the burning Il-2,” he was shot down again and made another emergency landing in the Donets River area and fell into the hands of the “Asians” - Soviet soldiers. Skillfully feigning injury and lulling the vigilance of careless soldiers, Hartman fled, jumping out of the back of the semi-truck that was carrying him, and returned to his own people that same day.

As a symbol of the forced separation from his beloved Ursula, Petch Hartman painted a bleeding heart pierced by an arrow on his plane and inscribed an “Indian” cry under the cockpit: “Karaya.”

Readers of German newspapers knew him as the “Black Devil of Ukraine” (the nickname was invented by the Germans themselves) and with pleasure or irritation (against the backdrop of the retreat of the German army) read about the ever-new exploits of this “promoted” pilot.

In total, Hartman was recorded 1404 sorties, 825 air battles, 352 victories were counted, of which 345 were Soviet aircraft: 280 fighters, 15 Il-2, 10 twin-engine bombers, the rest - U-2 and R-5.

Hartman was lightly wounded three times. As the commander of the 1st Squadron of the 52nd Fighter Squadron, which was based at a small airfield near Strakovnice in Czechoslovakia, at the end of the war Hartman knew (he saw the advancing Soviet units rising into the sky) that the Red Army was about to capture this airfield. He ordered the destruction of the remaining aircraft and headed west with all his personnel to surrender to the US Army. But by that time there was an agreement between the allies, according to which all Germans leaving the Russians should be transferred back at the first opportunity.

In May 1945, Major Hartman was handed over to the Soviet occupation authorities. At the trial, Hartmann insisted on his 352 victories, with emphatic respect, and defiantly recalled his comrades and the Fuhrer. About the progress of this trial was reported to Stalin, who spoke of the German pilot with satirical contempt. Hartman's self-confident position, of course, irritated the Soviet judges (the year was 1945), and he was sentenced to 25 years in the camps. The sentence under the laws of Soviet justice was commuted, and Hartman was sentenced to ten and a half years in prison camps. He was released in 1955.

Returning to his wife in West Germany, he immediately returned to aviation. He successfully and quickly completed a course of training on jet aircraft, and this time his teachers were Americans. Hartman flew the F-86 Saber jets and the F-104 Starfighter. The last aircraft during active operation in Germany turned out to be extremely unsuccessful and brought death to 115 German pilots in peacetime! Hartmann spoke disapprovingly and harshly of this jet fighter (which was completely fair), prevented its adoption by Germany and upset his relations with both the command of the Bundes-Luftwaffe and high-ranking American military officials. He was transferred to the reserve with the rank of colonel in 1970.

After being transferred to the reserve, he worked as an instructor pilot in Hangelaer, near Bonn, and performed in the aerobatic team of Adolf Galland “Dolfo”. In 1980, he became seriously ill and had to part with aviation.

It is interesting that the commander-in-chief of the Soviet and then Russian Air Force, Army General P. S. Deinekin, taking advantage of the warming of international relations in the late 80s - early 90s, several times persistently expressed his desire to meet with Hartman, but did not find mutual understanding with the German military officials.

Colonel Hartmann was awarded the Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds, the Iron Cross 1st and 2nd class, and the German Cross in Gold.

Gerhard Gerd Barkhorn, second Luftwaffe ace (Germany) - 301 air victories.

Gerhard Barkhorn was born in Königsberg, East Prussia, on March 20, 1919. In 1937, Barkhorn was accepted into the Luftwaffe as a fanen-junker (officer candidate rank) and began his flight training in March 1938. After completing his flight training, he was selected as a lieutenant and at the beginning of 1940 accepted into the 2nd Fighter Squadron "Richthofen", known for its old combat traditions, formed in the battles of the First World War.

Gerhard Barkhorn's combat debut in the Battle of Britain was unsuccessful. He did not shoot down a single enemy aircraft, but he himself twice left a burning car with a parachute, and once right over the English Channel. Only during the 120th flight (!), which took place on July 2, 1941, Barkhorn managed to open his account of his victories. But after that, his successes gained enviable stability. The hundredth victory came to him on December 19, 1942. On the same day, Barkhorn shot down 6 planes, and on July 20, 1942 - 5. He also shot down 5 planes before that, on June 22, 1942. Then the pilot’s performance decreased slightly - and he reached the two hundredth mark only on November 30, 1943.

Here's how Barkhorn comments on the enemy's actions:

“Some Russian pilots didn’t even look around and rarely looked back.

I shot down many who didn't even know I was there. Only a few of them were a match for European pilots; the rest did not have the necessary flexibility in air combat.”

Although it is not explicitly stated, from what we have read we can conclude that Barkhorn was a master of surprise attacks. He preferred dive attacks from the direction of the sun or approached from below from behind the tail of the enemy aircraft. At the same time, he did not avoid classic combat on turns, especially when he piloted his beloved Me-109F, even that version that was equipped with only one 15-mm cannon. But not all Russians succumbed so easily to the German ace: “Once in 1943, I endured a forty-minute battle with a stubborn Russian pilot and was unable to achieve any results. I was so wet with sweat, as if I had just stepped out of the shower. I wonder if it was as difficult for him as it was for me. The Russian flew a LaGG-3, and both of us performed all conceivable and inconceivable aerobatic maneuvers in the air. I couldn't reach him, and he couldn't reach me. This pilot belonged to one of the guards air regiments, which brought together the best Soviet aces.”

It should be noted that a one-on-one air battle lasting forty minutes was almost a record. There were usually other fighters nearby ready to intervene, or on those rare occasions when two enemy aircraft actually met in the sky, one of them usually already had the advantage in position. In the battle described above, both pilots fought, avoiding unfavorable positions for themselves. Barkhorn was wary of enemy actions (perhaps his experience in combat with RAF fighters had a strong influence here), and the reasons for this were as follows: firstly, he achieved his many victories by flying more sorties than many other experts; secondly, during 1,104 combat missions, with 2,000 flying hours, his plane was shot down nine times.

On May 31, 1944, with 273 victories to his name, Barkhorn was returning to his airfield after completing a combat mission. During this flight, he came under attack from a Soviet Airacobra, was shot down and wounded in the right leg. Apparently, the pilot who shot down Barkhorn was the outstanding Soviet ace Captain F. F. Arkhipenko (30 personal and 14 group victories), later Hero of the Soviet Union, who on that day was credited with victory over the Me-109 in his fourth combat mission. Barkhorn, who was making his 6th sortie of the day, managed to escape, but was out of action for four long months. After returning to service with JG 52, he brought his personal victories to 301, and was then transferred to the Western Front and appointed commander of JG 6 Horst Wessel. Since then, he has had no more success in air battles. Soon enlisted in Galland's strike group JV 44, Barkhorn learned to fly Me-262 jets. But already on the second combat mission, the plane was hit, lost thrust, and Barkhorn was seriously injured during a forced landing.

In total, during the Second World War, Major G. Barkhorn flew 1,104 combat missions.

Some researchers note that Barkhorn was 5 cm taller than Hartmann (about 177 cm tall) and 7-10 kg heavier.

He called his favorite machine the Me-109 G-1 with the lightest possible weapons: two MG-17 (7.92 mm) and one MG-151 (15 mm), preferring the lightness, and therefore the maneuverability of his vehicle, over the power of its weapons.

After the war, Germany's No. 2 ace returned to flying with the new West German Air Force. In the mid-60s, while testing a vertical takeoff and landing aircraft, he “dropped” and crashed his Kestrel. When the wounded Barkhorn was slowly and laboriously pulled out of the wrecked car, despite his severe injuries, he did not lose his sense of humor and muttered with force: “Three hundred and two...”

In 1975, G. Barkhorn retired with the rank of major general.

In winter, in a snowstorm, near Cologne on January 6, 1983, Gerhard Barkhorn and his wife were involved in a serious car accident. His wife died immediately, and he himself died in the hospital two days later - on January 8, 1983.

He was buried in the Durnbach War Cemetery in Tegernsee, Upper Bavaria.

Luftwaffe Major G. Barkhorn was awarded the Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords, the Iron Cross 1st and 2nd class, and the German Cross in Gold.

Gunter Rall - third Luftwaffe ace, 275 victories.

The third Luftwaffe ace in terms of the number of victories counted is Gunther Rall - 275 enemy aircraft shot down.

Rall fought against France and England in 1939–1940, then in Romania, Greece and Crete in 1941. From 1941 to 1944 he fought on the Eastern Front. In 1944, he returned to the skies of Germany and fought against the aircraft of the Western Allies. All his rich combat experience was gained as a result of more than 800 “rabarbars” (air battles) carried out on the Me-109 of various modifications - from Bf 109 B-2 to Bf 109 G-14. Rall was seriously wounded three times and shot down eight times. On November 28, 1941, in an intense air battle, his plane was so badly damaged that during an emergency belly landing, the car simply fell apart, and Rall broke his spine in three places. There was no hope left for returning to duty. But after ten months of treatment in the hospital, where he met his future wife, he was nevertheless restored to health and declared fit for flying work. At the end of July 1942, Rall took his plane into the air again, and on August 15 he scored his 50th victory over Kuban. On September 22, 1942, he chalked up his 100th victory. Subsequently, Rall fought over the Kuban, over the Kursk Bulge, over the Dnieper and Zaporozhye. In March 1944, he exceeded the achievement of V. Novotny, chalking up 255 aerial victories and leading the list of Luftwaffe aces until August 20, 1944. On April 16, 1944, Rall won his last, 273rd, victory on the Eastern Front.

As the best German ace of the time, he was appointed commander of II by Goering. / JG 11, which was part of the Reich air defense and armed with the “109” new modification - G-5. Defending Berlin in 1944 from British and American raids, Rall repeatedly came into battle with US Air Force aircraft. One day, “Thunderbolts” tightly pinned his plane over the capital of the Third Reich, damaging his control, and one of the bursts fired at the cockpit cut off thumb on the right hand. Rall was shell-shocked, but returned to duty a few weeks later. In December 1944, he headed the training school for Luftwaffe fighter commanders. In January 1945, Major G. Rall was appointed commander of the 300th Fighter Group (JG 300), armed with the FV-190D, but he did not win any more victories. It was difficult to imagine a victory over the Reich - downed planes fell over German territory and only then received confirmation. It’s not at all like in the Don or Kuban steppes, where a report of victory, confirmation from a wingman and a statement on several printed forms was enough.

During his combat career, Major Rall flew 621 combat missions and recorded 275 “downed” aircraft, of which only three were shot down over the Reich.

After the war, when the new German army, the Bundeswehr, was created, G. Rall, who did not think of himself as anything other than a military pilot, joined the Bundes-Luftwaffe. Here he immediately returned to flying work and mastered the F-84 Thunderjet and several modifications of the F-86 Saber. The skill of Major and then Oberst-Lieutenant Rall was highly appreciated by American military experts. At the end of the 50s he was appointed to the Bundes-Luftwaffe Art. an inspector supervising the retraining of German pilots for the new supersonic fighter F-104 Starfighter. The retraining was successfully carried out. In September 1966, G. Rall was awarded the rank of brigadier general, and a year later - major general. At that time, Rall led the fighter division of the Bundes-Luftwaffe. In the late 1980s, Lieutenant General Rall was dismissed from the Bundes-Luftwaffe as Inspector General.

G. Rall came to Russia several times and communicated with Soviet aces. On the Hero of the Soviet Union, Major General of Aviation G. A. Baevsky, who knew German well and communicated with Rall at the aircraft show in Kubinka, this communication made a positive impression. Georgy Arturovich found Rall’s personal position to be quite modest, including regarding his three-digit account, and as an interlocutor, he was an interesting person who deeply understood the concerns and needs of pilots and aviation.

Günther Rall died on October 4, 2009. Lieutenant General G. Rall was awarded the Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords, the Iron Cross 1st and 2nd class, the German Cross in gold; Great Federal Cross of the Worthy with Star (cross of the VI degree from the VIII degrees); Order of the Legion of Worth (USA).

Adolf GALLAND - outstanding organizer of the Luftwaffe, recording 104 victories on the Western Front, Lieutenant General.

Gently bourgeois in his refined habits and actions, he was a versatile and courageous man, an exceptionally gifted pilot and tactician, and enjoyed the favor of political leaders and the highest authority among German pilots, and yet they left their bright mark on the history of the world wars of the 20th century.

Adolf Galland was born into the family of a manager in the town of Westerholt (now within the boundaries of Duisburg) on March 19, 1912. Galland, like Marseille, had French roots: his Huguenot ancestors fled France in the 18th century and settled on the estate of Count von Westerholt. Galland was the second oldest of his four brothers. Upbringing in the family was based on strict religious principles, while the severity of the father significantly softened the mother. From an early age, Adolf became a hunter, catching his first trophy - a hare - at the age of 6 years. An early passion for hunting and hunting successes are also characteristic of some other outstanding fighter pilots, in particular A.V. Vorozheikin and E.G. Pepelyaev, who found in hunting not only entertainment, but also a significant help for their meager diet. Of course, the acquired hunting skills - the ability to hide, shoot accurately, follow the trail - had a beneficial effect on the formation of the character and tactics of future aces.

In addition to hunting, the energetic young Galland was actively interested in technology. This interest led him to the Gelsenkirchen gliding school in 1927. Graduating from gliding school and acquiring the ability to soar, find and select air currents was very useful for the future pilot. In 1932, after graduating from high school, Adolf Galland entered the German Air Transport School in Braunschweig, from which he graduated in 1933. Soon after graduating from school, Galland received an invitation to short-term courses for military pilots, secret in Germany at that time. After completing the courses, Galland was sent to Italy for an internship. Since the fall of 1934, Galland flew as co-pilot on the passenger Junkers G-24. In February 1934, Galland was drafted into the army, in October he was awarded the rank of lieutenant and sent to instructor service in Schleichsheim. When the creation of the Luftwaffe was announced on March 1, 1935, Galland was transferred to the 2nd Group of the 1st Fighter Squadron. Possessing an excellent vestibular apparatus and impeccable vasomotor skills, he quickly became an excellent aerobatic pilot. During those years, he suffered several accidents that almost cost him his life. Only exceptional persistence, and sometimes cunning, allowed Galland to remain in aviation.

In 1937, he was sent to Spain, where he flew 187 attack missions in a Xe-51B biplane. He had no aerial victories. For battles in Spain he was awarded the German Spanish Cross in gold with Swords and Diamonds.

In November 1938, upon returning from Spain, Galland became a commander of JG433, re-equipped with the Me-109, but before the outbreak of hostilities in Poland he was sent to another group armed with XSh-123 biplanes. In Poland, Galland flew 87 combat missions and received the rank of captain.

On May 12, 1940, Captain Galland won his first victories, shooting down three British Hurricanes at once on the Me-109. By June 6, 1940, when he was appointed commander of the 3rd Group of the 26th Fighter Squadron (III./JG 26), Galland had 12 victories to his name. On 22 May he shot down the first Spitfire. On August 17, 1940, at a meeting at Goering's Karinhalle estate, Major Galland was appointed commander of the 26th squadron. On September 7, 1940, he took part in a massive Luftwaffe raid on London, consisting of 648 fighters covering 625 bombers. For the Me-109, this was a flight almost to the maximum range; more than two dozen Messerschmitts on the way back, over Calais, ran out of fuel, and their planes fell into the water. Galland also had problems with fuel, but his car was saved by the skill of the glider pilot sitting in it, who reached the French coast.

On September 25, 1940, Galland was summoned to Berlin, where Hitler presented him with the third ever Oak Leaves to the Knight's Cross. Galland, in his words, asked the Fuhrer not to “belittle the dignity of the British pilots.” Hitler unexpectedly immediately agreed with him, saying that he regretted that England and Germany did not act together as allies. Galland fell into the hands of German journalists and quickly became one of the most “promoted” figures in Germany.

Adolf Galland was an avid cigar smoker, consuming up to twenty cigars daily. Even Mickey Mouse, who invariably adorned the sides of all his combat vehicles, was invariably depicted with a cigar in his mouth. In the cockpit of his fighter there was a lighter and a cigar holder.

On the evening of October 30, having declared the destruction of two Spitfires, Galland chalked up his 50th victory. On November 17, having shot down three Hurricanes over Calais, Galland took first place among the Luftwaffe aces with 56 victories. After his 50th claimed victory, Galland was promoted to the rank of lieutenant colonel. A creative man, he proposed several tactical innovations, which were subsequently adopted by most armies of the world. Thus, he considered the most successful option for escorting bombers, despite the protests of the “bombers,” to be a free “hunt” along their flight route. Another of his innovations was the use of a headquarters air unit, staffed by a commander and the most experienced pilots.

After May 19, 1941, when Hess flew to England, raids on the island practically ceased.

On June 21, 1941, the day before the attack on the Soviet Union, Galland's Messerschmitt, which had been staring at the Spitfire it had shot down, was shot down in a frontal attack from above by another Spitfire. Galland was wounded in the side and arm. With difficulty he managed to open the jammed canopy, unhook the parachute from the antenna post and land relatively safely. It is interesting that on the same day, at about 12.40, Galland’s Me-109 was already shot down by the British, and they crash-landed it “on its belly” in the Calais area.

When Galland was taken to the hospital in the evening of the same day, a telegram arrived from Hitler, saying that Lieutenant Colonel Galland was the first in the Wehrmacht to be awarded the Swords to the Knight's Cross, and an order containing a ban on Galland's participation in combat missions. Galland did everything possible and impossible to circumvent this order. On August 7, 1941, Lieutenant Colonel Galland scored his 75th victory. On November 18, he announced his next, already 96th, victory. On November 28, 1941, after the death of Mölders, Goering appointed Galland to the post of inspector of fighter aircraft of the Luftwaffe, and he was awarded the rank of colonel.

On January 28, 1942, Hitler presented Galland with the Diamonds for his Knight's Cross with Swords. He became the second recipient of this highest award in Nazi Germany. On December 19, 1942, he was awarded the rank of major general.

On May 22, 1943, Galland flew the Me-262 for the first time and was amazed by the emerging capabilities of the turbojet. He insisted on the speedy combat use of this aircraft, assuring that one Me-262 squadron was equal in strength to 10 conventional ones.

With the inclusion of US aircraft in the air war and the defeat in the Battle of Kursk, Germany's position became desperate. On June 15, 1943, Galland, despite strong objections, was appointed commander of the fighter aircraft of the Sicily group. They tried to save the situation in Southern Italy with Galland's energy and talent. But on July 16, about a hundred American bombers attacked the Vibo Valentia airfield and destroyed the Luftwaffe fighter aircraft. Galland, having surrendered command, returned to Berlin.

The fate of Germany was sealed, and neither the dedication of the best German pilots nor the talent of outstanding designers could save it.

Galland was one of the most talented and sensible generals of the Luftwaffe. He tried not to expose his subordinates to unjustified risks and soberly assessed the developing situation. Thanks to the accumulated experience, Galland managed to avoid major losses in the squadron entrusted to him. An outstanding pilot and commander, Galland had a rare talent for analyzing all the strategic and tactical features of a situation.

Under the command of Galland, the Luftwaffe carried out one of the most brilliant operations to provide air cover for ships, codenamed “Thunderstrike”. The fighter squadron under the direct command of Galland covered from the air the exit from the encirclement of the German battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, as well as the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen. Having successfully carried out the operation, the Luftwaffe and the fleet destroyed 30 British aircraft, losing 7 aircraft. Galland called this operation the "finest hour" of his career.

In the fall of 1943 - spring of 1944, Galland secretly flew more than 10 combat missions on the FV-190 A-6, chalking up two American bombers. On December 1, 1944, Galland was awarded the rank of lieutenant general.

After the failure of Operation Bodenplatte, when about 300 Luftwaffe fighters were lost, at the cost of 144 British and 84 American aircraft, Goering removed Galland from his post as inspector of fighter aircraft on January 12, 1945. This caused the so-called fighter mutiny. As a result, several German aces were demoted, and Galland was placed under house arrest. But soon a bell rang in Galland’s house: Hitler’s adjutant von Belof told him: “The Fuhrer still loves you, General Galland.”

In the conditions of a disintegrating defense, Lieutenant General Galland was instructed to form a new fighter group from the best aces of Germany and fight enemy bombers on the Me-262. The group received the semi-mystical name JV44 (44 as half of the number 88, which designated the number of the group that successfully fought in Spain) and entered combat in early April 1945. As part of JV44, Galland scored 6 victories, was shot down (landed across the runway) and wounded on April 25, 1945.

In total, Lieutenant General Galland flew 425 combat missions and chalked up 104 victories.

On May 1, 1945, Galland and his pilots surrendered to the Americans. In 1946–1947, Galland was recruited by the Americans to work in the historical department of the American Air Force in Europe. Later, in the 60s, Galland gave lectures in the United States on the actions of German aviation. In the spring of 1947, Galland was released from captivity. Galland spent this difficult time for many Germans on the estate of his old admirer, the widowed Baroness von Donner. He divided it between household chores, wine, cigars and hunting, which was illegal at that time.

During the Nuremberg trials, when Goering's defenders drew up a lengthy document and, trying to sign it from the leading figures of the Luftwaffe, brought it to Galland, he carefully read the paper and then decisively tore it from top to bottom.

“I personally welcome this trial because this is the only way we can find out who is responsible for all of this,” Galland allegedly said at the time.

In 1948, he met with his old acquaintance - the German aircraft designer Kurt Tank, who created the Focke-Wulf fighters and, perhaps, the best piston fighter in history - the Ta-152. Tank was about to sail to Argentina, where a big contract awaited him, and invited Galland to go with him. He agreed and, having received an invitation from President Juan Peron himself, soon sailed. Argentina, like the United States, emerged from the war incredibly rich. Galland received a three-year contract to reorganize the Argentine Air Force under the leadership of Argentine Commander-in-Chief Juan Fabri. The flexible Galland managed to find full contact with the Argentines and gladly passed on knowledge to those without combat experience pilots and their commanders. In Argentina, Galland flew almost every day on every type of aircraft he saw there, maintaining his flying shape. Soon Baroness von Donner and her children came to Galland. It was in Argentina that Galland began working on a book of memoirs, later called The First and the Last. A few years later, the Baroness left Galland and Argentina when he became involved with Sylvinia von Donhoff. In February 1954, Adolf and Sylvinia got married. For Galland, who was already 42 years old at that time, this was his first marriage. In 1955, Galland left Argentina and competed in aviation competitions in Italy, where he took an honorable second place. In Germany, the Minister of Defense invited Galland to retake the post of inspector - commander of the BundesLuftwaffe fighter aircraft. Galland asked for time to think it over. At this time, there was a change of power in Germany, the pro-American Franz Josef Strauss became Minister of Defense, who appointed General Kummhuber, an old enemy of Galland, to the post of inspector.

Galland moved to Bonn and went into business. He divorced Sylvinia von Donhoff and married his young secretary, Hannelise Ladwein. Soon Galland had children - a son, and three years later a daughter.

All his life, until the age of 75, Galland flew actively. When military aviation was no longer available to him, he found himself in light-engine and sport aviation. As Galland grew older, he devoted more and more time to meetings with his old comrades, with veterans. His authority among German pilots of all times was exceptional: he was an honorary leader of several aviation societies, president of the Association of German Fighter Pilots, and a member of dozens of flying clubs. In 1969, Galland saw and “attacked” the spectacular pilot Heidi Horn, who at the same time was the head of a successful company, and started a “fight” according to all the rules. He soon divorced his wife, and Heidi, unable to withstand the “dizzying attacks of the old ace,” agreed to marry 72-year-old Galland.

Adolf Galland, one of seven German fighter pilots awarded the Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves, Swords and Diamonds, as well as all the lower awards required by statute.

Otto Bruno Kittel - Luftwaffe ace No. 4, 267 victories, Germany.

This outstanding fighter pilot was nothing like, say, the arrogant and glamorous Hans Philipp, that is, he did not at all correspond to the image of an ace pilot created by the German Reich Ministry of Propaganda. A short, quiet and modest man with a slight stutter.

He was born in Kronsdorf (now Korunov in the Czech Republic) in the Sudetenland, then in Austria-Hungary, on February 21, 1917. Note that on February 17, 1917, the outstanding Soviet ace K. A. Evstigneev was born.

In 1939, Kittel was accepted into the Luftwaffe and was soon assigned to the 54th Squadron (JG 54).

Kitel announced his first victories on June 22, 1941, but in comparison with other Luftwaffe experts his start was modest. By the end of 1941, he had chalked up only 17 victories. At first, Kittel showed poor aerial shooting abilities. Then his senior comrades took over his training: Hannes Trauloft, Hans Philipp, Walter Nowotny and other pilots of the Green Heart air group. They didn't give up until their patience was rewarded. By 1943, Kittel had gained an eye and with enviable consistency began to record victories over Soviet aircraft one after another. His 39th victory, won on February 19, 1943, was the 4,000th victory claimed by the pilots of the 54th Squadron during the war.

When, under the crushing blows of the Red Army, German troops began to roll back to the west, German journalists found a source of inspiration in the modest but exceptionally gifted pilot Lieutenant Otto Kittel. Until mid-February 1945, his name did not leave the pages of German periodicals and regularly appears in military chronicles.

On March 15, 1943, after the 47th victory, Kittel was shot down and landed 60 km from the front line. In three days, without food or fire, he covered this distance (crossing Lake Ilmen at night) and returned to his unit. Kittel was awarded the German Cross in gold and the rank of chief sergeant major. On October 6, 1943, Chief Sergeant Major Kittel was awarded the Knight's Cross, received officer's buttonholes, shoulder straps and the entire 2nd Squadron of the 54th Fighter Group under his command. He was later promoted to chief lieutenant and awarded the Oak Leaves, and then the Swords for the Knight's Cross, which, as in most other cases, were presented to him by the Fuhrer. From November 1943 to January 1944 he was an instructor at the Luftwaffe flying school in Biarritz, France. In March 1944, he returned to his squadron, to the Russian front. Successes did not go to Kittel’s head: until the end of his life he remained a modest, hardworking and unassuming person.

Since the autumn of 1944, Kittel's squadron fought in the Courland "cauldron" in Western Latvia. On February 14, 1945, on his 583rd combat mission, he attacked an Il-2 group, but was shot down, probably from cannons. On that day, victories over the FV-190 were recorded by the pilots who piloted the Il-2 - the deputy squadron commander of the 806th attack air regiment, Lieutenant V. Karaman, and the lieutenant of the 502nd Guards Air Regiment, V. Komendat.

By the time of his death, Otto Kittel had 267 victories (of which 94 were IL-2), and he was fourth on the list of the most successful air aces in Germany and the most successful pilot who fought on the FV-190 fighter.

Captain Kittel was awarded the Knight's Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords, the Iron Cross 1st and 2nd class, and the German Cross in Gold.

Walter Nowi Novotny - Luftwaffe ace No. 5, 258 victories.

Although Major Walter Nowotny is considered the fifth-highest Luftwaffe ace in kills, he was the most famous ace of World War II during the war. Novotny ranked with Galland, Mölders and Graf in popularity abroad, his name was one of the few that became known behind the front lines during the war and was discussed by the Allied public, just as it was with Boelcke, Udet and Richthofen during the war. during the First World War.

Novotny enjoyed fame and respect among German pilots like no other pilot. For all his courage and obsession in the air, he was a charming and friendly man on the ground.